When a sudden, intense cramp hits the lower abdomen or flank, it can feel like a mini‑heart attack. If you’ve ever experienced that jolt and wondered whether it’s just a painful spasm or something far more serious, you’re not alone. Below is a practical guide that helps you decide when a urinary tract spasm turns into a medical emergency and what to expect at the hospital.

Quick Takeaways

- Seek emergency care if pain is crushing, lasts longer than 30 minutes, or is accompanied by fever, chills, or vomiting.

- Blood in urine (hematuria) or a sudden inability to pass urine are red‑flag signs.

- Common triggers include urinary tract infection, kidney stones, and catheter irritation.

- Emergency evaluation often involves a physical exam, blood work, and imaging such as a CT scan.

- After stabilization, follow‑up with a urologist can prevent future episodes.

What Is a Urinary Tract Spasm?

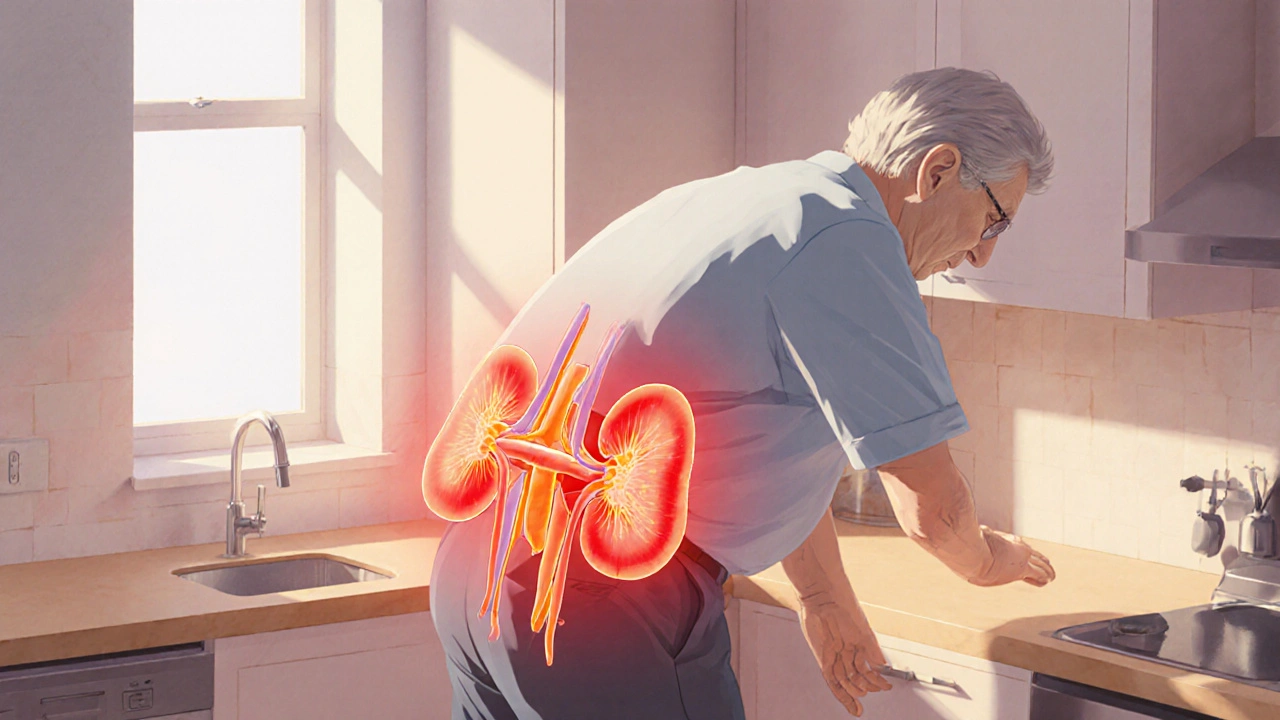

Urinary tract spasm is an involuntary, painful contraction of the smooth muscle lining the kidneys, ureters, bladder, or urethra. The spasm can be brief or persist for hours, and it often feels like a sharp, stabbing ache that radiates from the flank to the groin.

While the term itself isn’t widely used in everyday conversation, the phenomenon is a common symptom of several urologic conditions. Understanding the underlying cause is key to deciding whether you can wait for a routine doctor’s visit or need to head straight to the ER.

Common Triggers Behind the Pain

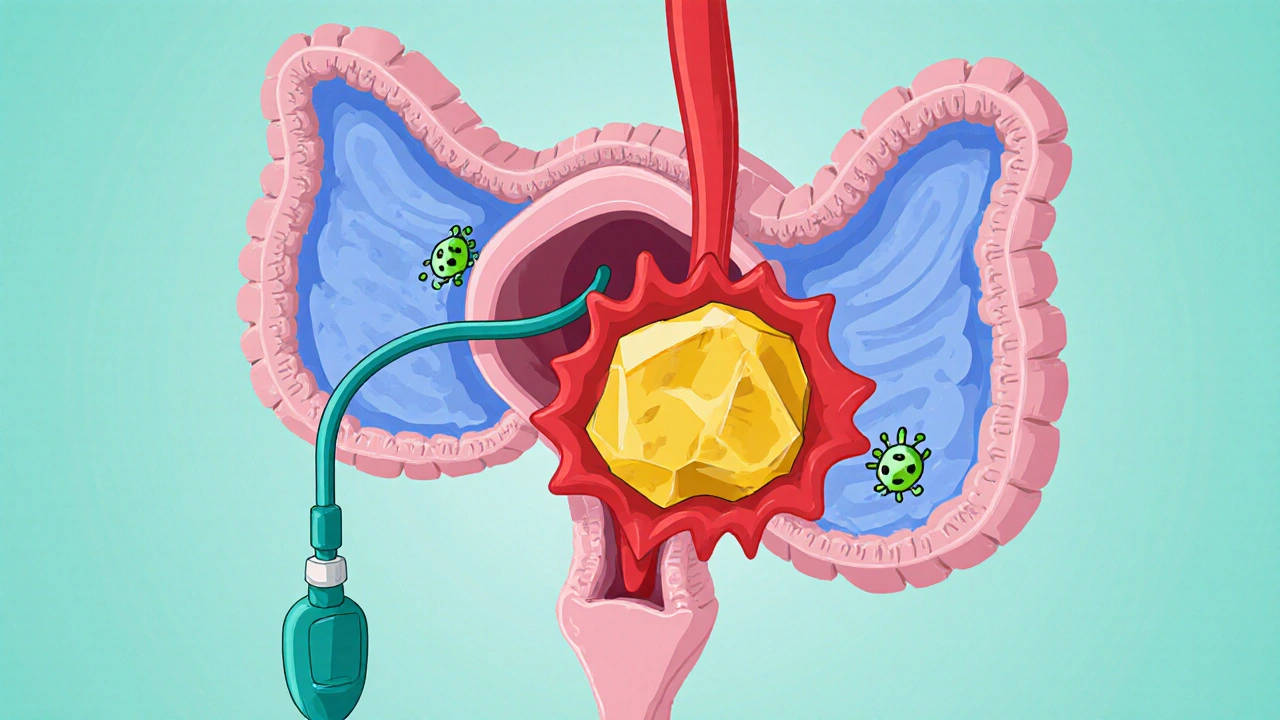

Several health issues can set off a urinary tract infection (UTI). The bacteria irritate the bladder wall, causing the muscle to contract forcefully. Another frequent culprit is a kidney stone. As the stone moves through the ureter, it acts like a tiny cork, prompting the surrounding muscle to spasm in an effort to push it out.

Other triggers include:

- Catheter placement or long‑term catheter use, which can irritate the urethra.

- Over‑distended bladder from holding urine too long.

- Neurological disorders that disrupt normal muscle signaling.

Typical Symptoms vs. Emergency Red‑Flag Signs

| Symptom | Usually Benign | Red‑Flag (Call 000/ER) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | Mild‑moderate, tolerable | Severe, crushing, or unrelenting for >30 min |

| Urine appearance | Clear, maybe slight odor | Blood (hematuria), cloudy, foul‑smelling hematuria |

| Fever/Chills | None or low‑grade (<38 °C) | Fever ≥38.5 °C, shaking chills |

| Vomiting | Rare | Persistent vomiting or inability to keep fluids down |

| Urine flow | Normal stream | Sudden inability to urinate (urinary retention) |

| Systemic signs | None | Rapid heartbeat, confusion, low blood pressure - signs of sepsis |

When to Seek Emergency Care

The safest rule of thumb is to trust your body’s alarm system. If any of the red‑flag symptoms above appear, head to the nearest emergency department without delay. Time matters most in two scenarios:

- Possible obstruction. A stone lodged in the ureter can block urine flow, raising pressure in the kidney and risking permanent damage.

- Systemic infection. An untreated UTI that spreads can cause sepsis, a life‑threatening condition that progresses quickly.

Even if you don’t see blood, a sudden, intense flank pain that radiates to the groin and is accompanied by nausea should still be evaluated urgently.

How Emergency Teams Evaluate the Problem

Upon arrival, the triage nurse will note your pain score, vital signs, and any visible urine abnormalities. The attending urologist (or an emergency physician with urology expertise) typically orders several tests:

- Blood work. Checks for infection (white‑blood‑cell count), kidney function (creatinine, BUN), and signs of sepsis.

- Urinalysis. Detects blood, bacteria, and crystals that hint at stones.

- Imaging. A non‑contrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the gold standard for spotting stones and assessing obstruction. In pregnant patients, an ultrasound is preferred.

- Catheter assessment. If you have an indwelling catheter, staff will inspect it for blockage or infection.

Based on the findings, the team decides whether you need immediate pain control, antibiotics, drainage of the urinary system, or even surgical intervention.

Immediate Management Options in the ER

While awaiting test results, clinicians can start several measures to ease the spasm and prevent complications:

- Intravenous fluids. Hydration helps flush out small stones and dilutes urine, reducing irritation.

- Pain relief. NSAIDs (e.g., ketorolac) or opiates are given intravenously for fast relief.

- Alpha‑blockers. Medications like tamsulosin relax the ureter’s muscle wall, facilitating stone passage.

- Antibiotics. If a urinary tract infection is suspected, broad‑spectrum IV antibiotics are started immediately.

In cases of complete urinary blockage, a temporary catheter or a nephrostomy tube may be placed to drain urine and relieve pressure.

Follow‑Up Care and Prevention

After you’re discharged, you’ll likely be asked to schedule a follow‑up appointment with a urology clinic. During that visit, the doctor will:

- Review imaging results and decide if further stone removal (e.g., lithotripsy) is needed.

- Prescribe a tailored antibiotic regimen if a UTI was confirmed.

- Offer lifestyle advice: increase fluid intake (aim for >2 L/day), limit salt and animal protein, and consider dietary calcium adjustments.

- Discuss preventive medications such as potassium citrate for certain stone types.

If you have a history of recurrent stones, a metabolic work‑up may be ordered to pinpoint the exact cause (e.g., hyperoxaluria, low urine volume).

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a urinary tract spasm happen without an underlying condition?

Occasionally, a spasm can be a one‑off event caused by temporary bladder over‑distention (like holding urine too long). However, most painful spasms have an identifiable trigger such as a stone, infection, or catheter irritation.

Is it safe to take over‑the‑counter painkillers at home?

For mild discomfort, ibuprofen or acetaminophen can help. But if the pain is severe, persistent, or comes with fever, a professional evaluation is essential because the underlying cause may need urgent treatment.

What does “hematuria” mean, and why is it an emergency sign?

Hematuria is the presence of blood in the urine. It can indicate a stone, a severe infection, or even trauma to the urinary tract. When accompanied by pain or fever, it signals that the kidney or bladder may be damaged and requires prompt assessment.

How quickly can a kidney stone pass on its own?

Small stones (<5 mm) often pass within a few days to a week with hydration and pain control. Larger stones (>7 mm) may need medical assistance such as lithotripsy or ureteroscopy.

What are the long‑term risks of repeated urinary tract spasms?

Repeated spasms can scar the ureter or bladder, leading to strictures that obstruct urine flow. Chronic infections increase the risk of kidney damage. Early diagnosis and preventive measures are essential to avoid these complications.

Shan Reddy

October 23, 2025 AT 16:33I've had a few nasty flank cramps after holding it too long, and the guide's red‑flag list saved me from waiting too long. Knowing that crushing pain for over half an hour or blood in the urine means a trip to the ER helped me act fast and avoid a bigger problem.

CASEY PERRY

October 23, 2025 AT 19:20Severe, unrelenting pain exceeding thirty minutes, accompanied by hematuria, warrants immediate emergency evaluation.

Naomi Shimberg

October 23, 2025 AT 22:06While the article outlines common red‑flags, it neglects to mention that transient spasms can occur in perfectly healthy individuals after excessive caffeine intake. Moreover, the binary categorisation of "benign" versus "emergency" oversimplifies a spectrum of clinical presentations. One must consider patient history, such as prior stone passage, before deeming a symptom emergent. The recommendation for immediate CT scanning may expose patients to unnecessary radiation, especially when ultrasound could suffice. Also, the focus on hematuria ignores the fact that microscopic blood may be present without serious pathology. A more nuanced approach would balance clinical judgement with diagnostic stewardship. Finally, the suggestion to "head straight to the ER" does not account for access disparities in rural settings. In sum, while useful, the guide could benefit from a broader perspective.

sara fanisha

October 24, 2025 AT 00:53Stay calm and remember that not every twinge needs a trip to the ER.

Tristram Torres

October 24, 2025 AT 03:40If you can tolerate the pain, you’re probably fine-no need to overreact.

Jinny Shin

October 24, 2025 AT 06:26Indeed, the previous point about immediate CT scans feels a bit dramatic. In many cases, supportive care and observation can be just as effective. Of course, when the pain is truly excruciating, swift imaging is justified, but we must weigh the risks.

deepak tanwar

October 24, 2025 AT 09:13While labs are useful, over‑reliance on imaging can expose patients to unnecessary radiation. An initial ultrasound can often differentiate between obstruction and infection without the costs and risks of a CT.

Simon Waters

October 24, 2025 AT 12:00They don’t tell you that most hospitals push CT scans to boost their revenue. A quick bedside ultrasound, when available, can spare you from the radiation and the extra bill.

Vikas Kumar

October 24, 2025 AT 14:46Our country’s top urologists can handle these cases without the baggage of foreign guidelines, focusing on patient‑centered care rather than protocol‑driven over‑testing.

Celeste Flynn

October 24, 2025 AT 17:33Kidney stone pain can mimic many other issues

First, stay hydrated and try to drink at least three liters a day

This helps flush tiny crystals before they become a problem

If you notice blood in your urine, that’s a sign to get checked out

Fever or chills suggest an infection and you should not wait

Over‑the‑counter pain meds can be a stop‑gap but not a cure

When pain is severe and lasts longer than thirty minutes, head to the ER

A CT scan will show the stone’s size and location

Sometimes an ultrasound is enough and avoids radiation

Remember that some stones pass on their own if they’re small

For larger stones, lithotripsy or ureteroscopy may be needed

After treatment, a metabolic work‑up can prevent recurrences

Dietary changes like reducing oxalate‑rich foods help too

Consult a urologist for a personalized plan

Never ignore red‑flag symptoms; early intervention saves kidneys

kenny lastimosa

October 24, 2025 AT 20:20Pain, like all sensations, is a message that our bodies send; ignoring it can lead to deeper discord.

Heather ehlschide

October 24, 2025 AT 23:06Even if you doubt the system, seeking care when red‑flags appear is still the safest choice.