How the TRIPS Agreement Blocks Generic Drugs for Millions

On January 1, 1995, a global rule changed forever how medicines are made and sold. The TRIPS Agreement is a World Trade Organization treaty that requires all member countries to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceutical products. At the time, it was sold as a way to encourage innovation. But for low- and middle-income countries, it became a barrier to survival.

Before TRIPS, countries like India and Brazil could make cheap copies of life-saving drugs. A year of HIV treatment cost $10,000 in the U.S. In India, it cost $87. That changed overnight. After TRIPS, patent laws locked those prices in. Generic versions disappeared. Millions couldn’t afford treatment.

Today, two billion people still lack regular access to essential medicines. Eighty percent of that gap is directly tied to patent rules. And the system designed to fix it - the so-called "flexibilities" - barely works.

What TRIPS Actually Requires

The TRIPS Agreement is a binding international treaty under the WTO that sets minimum standards for intellectual property protection. For medicines, that means:

- Every country must grant patents on new drugs for 20 years from the filing date (Article 33)

- Patents must cover chemical compounds, not just manufacturing methods (Article 27)

- Generic drug makers can’t start production until the patent expires

These rules sound fair on paper. But they ignore reality. A drug patent doesn’t mean a drug is better. It just means no one else can copy it. And for diseases like HIV, tuberculosis, or hepatitis C - which hit poor countries hardest - the cost difference between branded and generic versions is often 10 to 1,000 times.

For example, the HIV drug efavirenz cost $140 per patient per year when patented. After Thailand issued a compulsory license in 2006, the price dropped to $30. That’s not innovation. That’s just competition.

The Doha Declaration: A Promise That Wasn’t Kept

In 2001, the world acknowledged the problem. The Doha Declaration is a WTO statement affirming that public health emergencies override patent rights. It said countries could ignore patents to make or import generic drugs during crises.

That sounded like progress. But it came with a catch: you had to prove you were in a crisis. And even then, you had to jump through hoops.

Article 31 of TRIPS allows compulsory licensing - where a government forces a patent holder to let others make the drug. But there’s a twist: the license can only be used for the domestic market. That meant countries without drug factories were stuck. If you’re Rwanda and you need HIV meds but can’t make them yourself, TRIPS says you’re out of luck.

The Broken Workaround: Article 31bis

In 2005, the WTO tried to fix that. They created Article 31bis is a legal mechanism allowing countries without drug manufacturing to import generics made under compulsory license. Sounds simple, right?

It’s not.

To use it, you need to:

- Prove you have no manufacturing capacity

- Notify the WTO 15 days before import

- Get the exporting country to issue a special license

- Pay the patent holder "adequate remuneration" - which often means paying 70% of the branded price

- Track every pill to make sure it doesn’t leak into other markets

It took four years for Rwanda to get its first shipment of generic HIV drugs from Canada in 2008. Médecins Sans Frontières called it "unworkable." And guess what? It’s still the only time it’s ever been used.

Why? Because no country wants to be next. The U.S. has threatened trade sanctions against Thailand, Brazil, and South Africa for even trying. In 2007, Thailand lost $57 million a year in export benefits after issuing a license for heart and cancer drugs. The message was clear: don’t challenge the system.

Why Most Countries Never Use Flexibilities

A 2017 study looked at 105 low- and middle-income countries. Eighty-three percent had never issued a single compulsory license. Why?

- They don’t have lawyers who understand patent law

- They lack government staff dedicated to this work - on average, just 1.2 full-time employees per country

- They fear being labeled "uncooperative" by the U.S. or EU

- They’re pressured by pharmaceutical lobbyists

Some countries don’t even have laws allowing compulsory licensing. Of the 48 least-developed countries, 67% still didn’t have the legal tools to issue licenses in 2020 - even though they were granted a 2033 deadline to catch up.

And then there’s the legal risk. Between 2001 and 2021, 41% of compulsory licensing attempts were blocked by lawsuits from drug companies. Another 29% were dropped because of political pressure.

Voluntary Licensing: A Band-Aid, Not a Cure

Drug companies say they’re helping through "voluntary licensing." The Medicines Patent Pool is a UN-backed initiative where companies voluntarily allow generic makers to produce their drugs. It’s worked for HIV - covering 44 patented medicines in 118 countries.

But here’s the problem:

- It covers only 1.2% of all patented medicines globally

- 73% of those licenses are limited to sub-Saharan Africa, even though diseases like hepatitis C and diabetes affect patients everywhere

- Companies choose which drugs to license - and often exclude newer, more expensive ones

- They set the rules - not the patients

It’s charity, not justice. And it doesn’t touch the biggest killers: cancer drugs, diabetes meds, or mental health treatments.

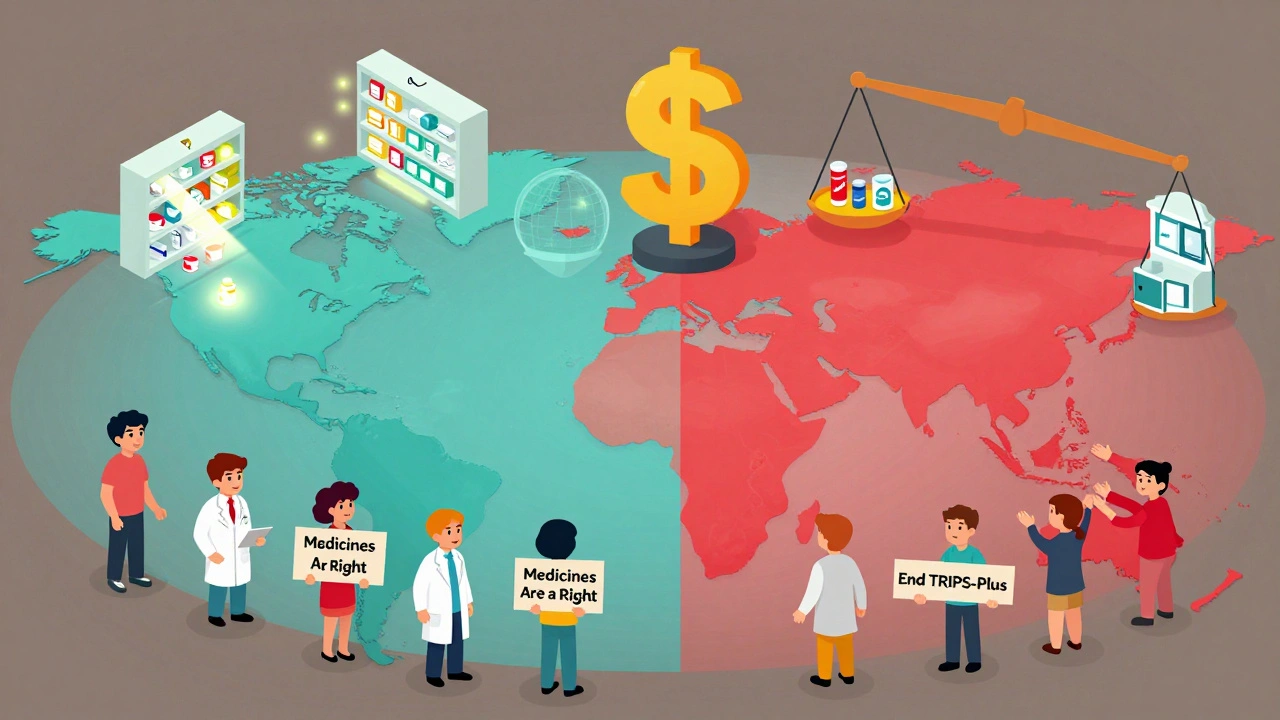

TRIPS-Plus: The Hidden Rules That Make Things Worse

Even if a country follows TRIPS, they’re still trapped. Because most now sign "TRIPS-plus" deals - side agreements with the U.S., EU, or Canada that add even stricter rules.

Examples:

- Extending patent terms beyond 20 years

- Blocking generic approval even after patent expires

- Requiring data exclusivity - meaning generic makers can’t use clinical trial data from the original drug for 5-10 years

The U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement added 10 years of extra protection for some drugs. Oxfam estimated these extra rules cost LMICs $2.3 billion a year in lost savings. That’s enough to treat millions of people.

As of 2021, 86% of WTO members have added TRIPS-plus provisions. The system isn’t broken - it’s being rigged.

What’s Changed Since COVID?

In 2020, India and South Africa asked the WTO to temporarily waive TRIPS rules for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. After two years of lobbying, the WTO agreed - but only for vaccines. Therapies, diagnostics, and future pandemics? Still locked down.

The 2022 waiver allowed some countries to make generic vaccines without permission. But it’s full of loopholes. Companies still control the technology. You can’t copy the vaccine unless you have the recipe. And few low-income countries have the labs to do it anyway.

Meanwhile, the UN’s 2024 Pandemic Agreement called for "reform of the TRIPS Agreement." But reform is slow. And the drug industry still spends billions lobbying against change.

The Real Cost of Patent Protection

Pharmaceutical companies made $1.42 trillion in 2022. Only 12% of prescriptions are for patented drugs. But they bring in 68% of the revenue. Why? Because they’re priced to maximize profit, not to save lives.

In the U.S., generics make up 89% of prescriptions. In low-income countries, they’re only 28%. The same pill - $1 in India, $100 in the U.S.

And it’s not just about money. It’s about time. A patient in Malawi waiting for a cancer drug that’s patented? They may not survive the 18-month wait for a legal workaround.

What Needs to Change

Here’s what actually works:

- Allow countries to import generics without complex WTO paperwork

- End TRIPS-plus provisions in trade deals

- Expand compulsory licensing to cover all medicines, not just HIV

- Fund public research so drugs are developed without patent monopolies

- Support local manufacturing in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America

The tools exist. The laws can be changed. The question is: who has the power to make it happen?

Right now, the system protects profits over people. And until that changes, millions will keep dying because a patent says they can’t have a cheap pill.

Can a country ignore TRIPS to make generic drugs?

Yes, but it’s risky. TRIPS allows compulsory licensing during public health emergencies under the Doha Declaration. Countries like Thailand and Brazil have done it. But they faced political pressure, trade threats, and legal challenges from drug companies. So while it’s legal, it’s not easy.

Why hasn’t the Article 31bis system been used more?

Because it’s too slow and too complicated. It took Rwanda four years to import one shipment of HIV drugs. The process requires 78 steps across two countries, legal notices, payment negotiations, and strict tracking. Most countries don’t have the staff or political will to go through it - especially when the U.S. threatens to cut trade benefits.

Are generic drugs safe?

Yes. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredients as branded ones and must meet the same quality standards. The WHO and U.S. FDA approve them. The difference is price - not safety. In India, generic antiretrovirals have saved over 10 million lives since 2000.

Why do pharmaceutical companies oppose generic access?

Because their business model depends on monopoly pricing. A drug patent lets them charge 10 to 1,000 times more than the cost of production. If generics enter the market, prices drop fast. That’s why companies spend millions lobbying against compulsory licenses and pushing for TRIPS-plus rules.

What’s the difference between TRIPS and TRIPS-plus?

TRIPS is the global minimum standard set by the WTO. TRIPS-plus are extra rules added in bilateral trade deals - like extending patent terms, blocking generic approval, or requiring data exclusivity. These are not required by TRIPS but are forced on weaker countries during trade negotiations.

Is there a legal way for poor countries to make their own generic drugs?

Yes - through compulsory licensing under TRIPS Article 31. But only if they have manufacturing capacity. For countries without factories, the Article 31bis system exists - but it’s so complex and politically risky that it’s only worked once. The real solution is building local production and removing trade threats.

How do patents affect access to cancer drugs?

Cancer drugs are among the most expensive. A single course of imatinib (Glivec) cost $30,000 a year in the U.S. After India issued a compulsory license, a generic version cost $200. But most countries can’t access these generics because of patent barriers. As a result, cancer survival rates in low-income countries are often half those in rich nations.

What role does the Medicines Patent Pool play?

The Medicines Patent Pool helps negotiate voluntary licenses with drug companies so generics can be made for HIV, hepatitis C, and some COVID treatments. But it only covers 44 out of thousands of patented medicines. It’s useful, but it’s not a right - it’s a favor granted by corporations.

What Comes Next?

The next decade will decide whether TRIPS remains a tool for corporate profit - or becomes a framework for human survival.

Right now, 58 countries are negotiating new trade deals that include TRIPS-plus clauses. The UN projects that without reform, medicine access gaps will affect 3.2 billion people by 2030.

Change won’t come from courts or treaties alone. It will come from pressure - from activists, from governments, from patients demanding the right to live. The law says patents are legal. But it never said human lives are optional.

Taya Rtichsheva

December 11, 2025 AT 04:51why are we still pretending this is about innovation and not profit?

Christian Landry

December 12, 2025 AT 08:58we spend billions on war but can't afford to let people take medicine that costs $3 to make?

someone's making bank while kids in Malawi die waiting for a pill

someone please fix this

Mona Schmidt

December 13, 2025 AT 16:52Sarah Gray

December 15, 2025 AT 00:29Suzanne Johnston

December 16, 2025 AT 13:42Graham Abbas

December 18, 2025 AT 04:28Meanwhile, Big Pharma made more profit in one quarter than the entire GDP of Rwanda.

They call it 'free trade'-but it's really 'free exploitation'.

Evelyn Pastrana

December 19, 2025 AT 08:12and then you get mad when a country says 'nah we're making it for $30'

you're not saving lives-you're just selling hope at 1000x markup

George Taylor

December 20, 2025 AT 17:33Every time someone tries to 'fix' this, they end up destroying innovation...

And then... people die...

But... it's the corporations' fault...

Right?...

Wait...

Who even made the drugs in the first place...

Who paid for the trials...

Who took the risks...

It's... so... complicated...

Why can't we just... leave it alone...

It's not like we can just... fix everything...

Right?

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

December 22, 2025 AT 06:22Guylaine Lapointe

December 22, 2025 AT 23:34Andrea Petrov

December 24, 2025 AT 00:23Tejas Bubane

December 24, 2025 AT 15:21Ajit Kumar Singh

December 26, 2025 AT 09:05Where was this ethics when we were colonized?

Where was this ethics when they stole our resources?

Now they want us to pay for the same medicine they stole the formula for?

Carina M

December 28, 2025 AT 00:07