Drug shortages are no longer rare emergencies-they’re a constant pressure on hospitals and clinics

It’s 3 a.m. in a busy emergency room. A patient comes in with septic shock. The go-to antibiotic, meropenem, is out of stock. The backup? Also gone. The team scrambles for alternatives, delaying treatment by hours. This isn’t a worst-case scenario from a movie. It’s happening in hospitals across the U.S., Australia, and Europe every week in 2026.

Drug shortages aren’t just about running out of pills. They force doctors to use less effective drugs, increase patient risk, and drive up costs. In 2024, the FDA recorded over 300 active drug shortages-up 40% from 2020. And it’s not just antibiotics or cancer drugs. Even basic IV fluids, insulin, and common painkillers are affected.

So what are health systems actually doing to stop this?

Stockpiling isn’t just for hurricanes anymore

Before 2020, most hospitals kept just enough drug inventory to last a few days. Now, the smart ones are holding 30 to 60 days of critical meds. It’s expensive, but cheaper than losing a patient because you couldn’t get a life-saving drug.

Hospitals like Cleveland Clinic and Intermountain Health now use predictive analytics to forecast shortages before they happen. They track global manufacturing delays, raw material shortages, and even weather patterns that could disrupt production. If a supplier in India reports a factory shutdown, the hospital’s pharmacy team gets an alert. They don’t wait for the shelves to go empty-they order ahead.

Some systems have even started buying directly from manufacturers instead of through distributors. This cuts out middlemen, reduces delays, and gives hospitals more control. Kaiser Permanente, for example, now sources 15% of its essential drugs this way-a move that cut supply chain delays by 41% in 2024.

Alternative sourcing: when the usual suppliers fail

When a drug disappears, hospitals don’t just sit around. They look for alternatives-legally and safely.

Many are turning to FDA-approved generic manufacturers outside the usual supply chains. In 2023, a shortage of the blood thinner heparin forced dozens of U.S. hospitals to switch to a Canadian supplier. It wasn’t ideal, but it worked. The FDA fast-tracked approval for this alternative, and hospitals avoided a crisis.

Some systems are building relationships with smaller, regional compounding pharmacies. These labs can make small batches of critical drugs that are in short supply. In Australia, several public hospitals now partner with licensed compounding labs in Sydney and Melbourne to produce sterile injectables like morphine and midazolam when national supplies drop.

And yes-some hospitals are even importing drugs from countries with looser regulations, under special FDA or TGA exemptions. It’s risky, but when a child needs a drug that doesn’t exist locally, they do it.

Using technology to stretch what you have

Technology isn’t just about AI chatbots. In pharmacies, it’s about making every dose count.

Hospitals are using AI to monitor drug usage in real time. If a unit starts using 30% more of a certain drug than usual, the system flags it. Maybe it’s a new protocol. Maybe it’s waste. Either way, they catch it early.

Some systems are using automated dispensing machines that don’t just hand out pills-they track every single tablet. If a nurse takes 10 vials of a drug in one shift, the system asks: Why? Is this normal? Is there a shortage elsewhere?

And then there’s the big one: repurposing. When a drug is in short supply, pharmacists look at its chemical structure and ask: Can we substitute another drug with similar properties? In 2024, a shortage of propofol led some hospitals to use ketamine as an alternative for sedation. It wasn’t perfect, but it saved lives.

Team-based care: letting nurses and PAs do more

Doctors can’t be everywhere. But nurses, physician assistants, and pharmacists can fill the gaps-if they’re allowed to.

More hospitals are expanding the scope of practice for nurse practitioners. In 2025, 72% of U.S. hospitals let NPs prescribe controlled substances without physician oversight for stable chronic conditions. That means fewer bottlenecks when a patient needs a refill on a shortage-hit drug.

Pharmacists are now embedded in clinical teams-not just behind the counter. At Mayo Clinic, pharmacists review every patient’s meds before discharge. If a drug is unavailable, they immediately suggest a safe alternative, adjust dosing, or coordinate with the pharmacy to get it delivered within 24 hours.

This isn’t just about efficiency. It’s about safety. A 2024 Johns Hopkins study found that hospitals with pharmacist-led medication teams had 38% fewer adverse events during drug shortages.

Building resilience, not just reacting

The best health systems aren’t just fixing shortages-they’re preventing them.

Some are investing in domestic manufacturing. The U.S. government’s 2024 Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Resilience Act gave $1.2 billion in grants to companies building drug production facilities inside the country. Companies like Pfizer and Teva are using that money to expand U.S.-based production of antibiotics and injectables.

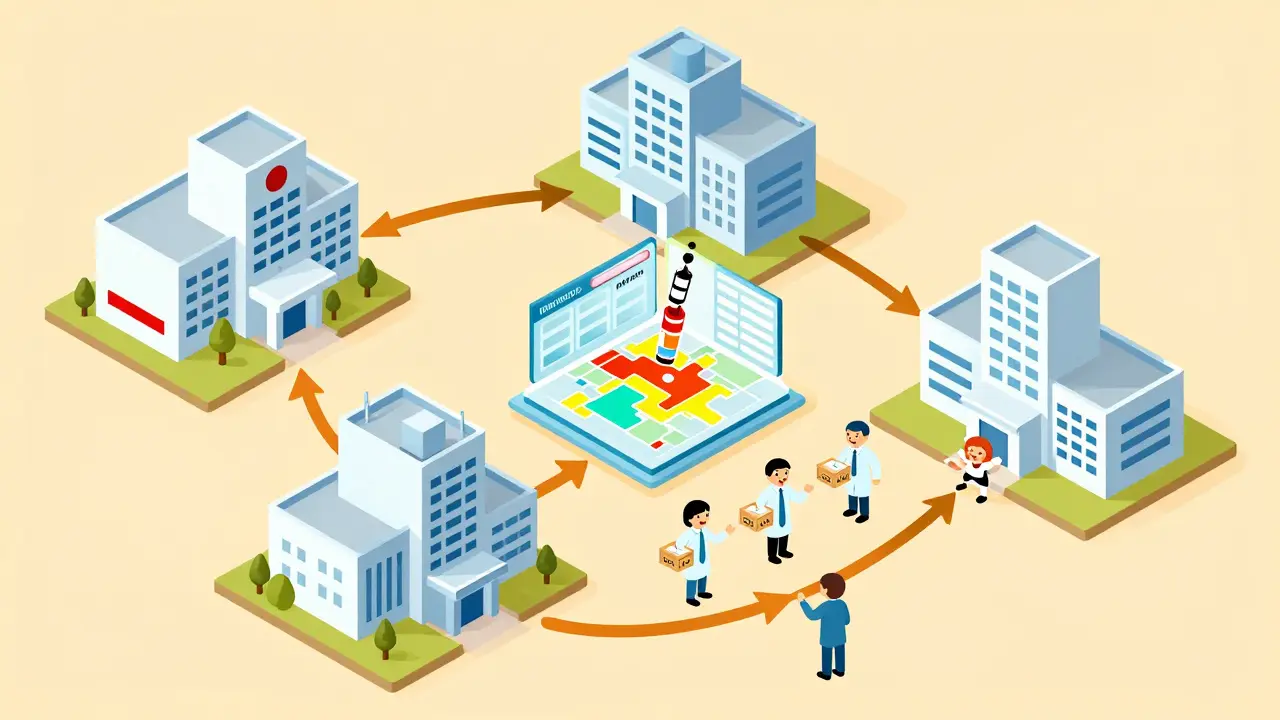

Others are forming regional alliances. In Australia, 12 major public hospitals in New South Wales now share a centralized drug inventory system. If one hospital runs low, another can transfer stock within hours. No waiting for delivery. No scrambling.

And then there’s policy. Hospitals are lobbying for changes. They want faster FDA approvals for generic drugs. They want to remove barriers to importing safe alternatives. They want to stop the practice of manufacturers discontinuing low-profit drugs-like old antibiotics-because they’re not lucrative enough.

What’s still broken

Let’s be honest: most of these fixes are patchwork. The system is still fragile.

Small rural hospitals can’t afford AI systems or stockpiles. Community clinics still rely on one distributor. When that distributor has a problem, they’re out of luck.

And global supply chains? Still a mess. Over 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients still come from China and India. One factory fire, one political dispute, one shipping delay-and the whole chain stumbles.

Worse, there’s no national tracking system in most countries. No one knows exactly how much of a drug is left in the entire country. Hospitals guess. Patients suffer.

What works-and what doesn’t

Here’s what the data says works:

- Stockpiling critical drugs - Reduces emergency responses by 50%

- Pharmacist-led teams - Cuts medication errors during shortages by 40%

- Regional sharing networks - Lowers local shortages by 60%

- Domestic manufacturing incentives - Increases supply reliability by 35% in 2 years

Here’s what doesn’t:

- Waiting until the last minute to order

- Using unapproved or unverified foreign suppliers

- Ignoring pharmacist input

- Assuming a drug will always be available

What patients can do

You can’t control the supply chain. But you can be prepared.

- Ask your doctor: Is there a generic or alternative drug if this one runs out?

- Keep a list of your meds-name, dose, why you take it. If a drug is unavailable, this helps your pharmacist find a substitute.

- Don’t hoard. Taking extra pills just makes shortages worse for others.

- Report shortages to your pharmacy or local health department. Data matters.

The future: smarter, local, and shared

By 2027, the most resilient health systems won’t just react to shortages-they’ll prevent them.

Think local manufacturing hubs. Real-time national drug inventory dashboards. AI that predicts shortages weeks in advance. Pharmacists as frontline decision-makers.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s resilience. The ability to keep giving patients the drugs they need-even when the world is falling apart.

Why are drug shortages getting worse?

Drug shortages are worsening because global supply chains are fragile, manufacturing is concentrated in just a few countries, and many drugmakers stop producing low-profit medications. When one factory shuts down-due to quality issues, natural disasters, or political issues-the whole system feels it. Plus, there’s no real-time tracking of drug inventory across countries, so shortages go unnoticed until hospitals are empty.

Can I trust generic drugs during a shortage?

Yes. Generic drugs must meet the same FDA and TGA standards as brand-name drugs. They have the same active ingredients, strength, and effectiveness. During shortages, switching to a generic is often the safest and most reliable option. If your pharmacy suggests a generic, ask them to confirm it’s approved and equivalent.

Are there any drugs that are always in short supply?

Yes. Antibiotics like meropenem and vancomycin, cancer drugs like cisplatin and doxorubicin, and injectables like propofol and insulin are consistently at risk. These are complex to make, have low profit margins, or rely on a single global supplier. They’re also critical-so when they’re gone, the impact is huge.

How do hospitals decide which drug to use when one is unavailable?

Hospitals use clinical guidelines developed by pharmacists and physicians. They look at drug equivalence, safety data, and patient history. For example, if one sedative is out, they might switch to another with similar effects. They avoid untested alternatives. The goal is to match the clinical outcome as closely as possible-without risking patient safety.

What’s being done to make drug production more reliable?

Governments are funding domestic manufacturing, especially for critical drugs. The U.S. and Australia are investing billions to bring production back home. Hospitals are also partnering with regional compounding labs and building regional drug-sharing networks. Long-term, the goal is to have multiple suppliers for every essential drug-not just one.

Alec Stewart Stewart

February 4, 2026 AT 00:56Samuel Bradway

February 4, 2026 AT 22:27Caleb Sutton

February 6, 2026 AT 10:44pradnya paramita

February 7, 2026 AT 14:37Jamillah Rodriguez

February 8, 2026 AT 21:55Susheel Sharma

February 9, 2026 AT 21:16Prajwal Manjunath Shanthappa

February 10, 2026 AT 16:19Alex LaVey

February 12, 2026 AT 01:27Joy Johnston

February 12, 2026 AT 18:22Shelby Price

February 13, 2026 AT 14:00Nathan King

February 15, 2026 AT 00:11rahulkumar maurya

February 15, 2026 AT 19:31