Opioid Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps you identify risk factors for opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) based on evidence-based criteria from the article. OIRD is a silent, life-threatening condition that often goes unnoticed until it's too late.

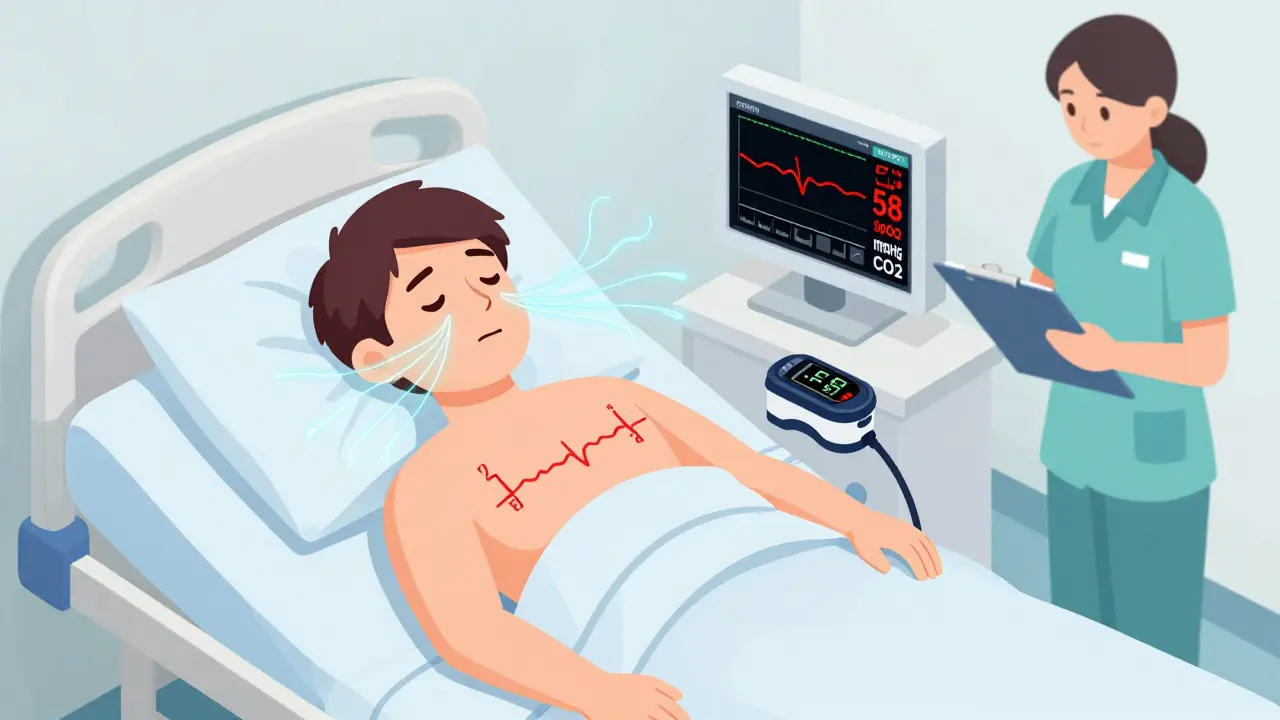

What respiratory depression actually looks like - and why it’s silent until it’s too late

Most people think of an overdose as someone collapsing, gasping, or unresponsive. But in reality, the most dangerous opioid reactions start quietly. A patient in recovery might seem calm, even sleeping peacefully. Their skin looks normal. Their pulse is steady. But their breathing? It’s slowing down - one breath every 12 seconds, then 15, then 20. Oxygen levels stay high because they’re on supplemental oxygen. No alarm sounds. No one notices. By the time they turn blue, it’s often too late.

This is opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD). It’s not a rare accident. It’s a predictable, preventable event that kills people every day - often in hospitals, nursing homes, and even at home after a routine surgery. The key isn’t just knowing opioids are dangerous. It’s recognizing the specific signs that tell you breathing is failing - before the body shuts down.

The exact signs of opioid-induced respiratory depression

Respiratory depression isn’t just slow breathing. It’s a cluster of physiological failures. The brainstem, which controls automatic breathing, gets suppressed by opioids. The body stops responding to rising carbon dioxide or falling oxygen. That’s what makes it so deadly.

- Respiratory rate below 8 breaths per minute - this is the red line. Normal is 12-20. Below 10 is warning. Below 8 is emergency.

- Shallow, irregular breaths - not deep, full breaths. Think tiny, weak puffs of air.

- Oxygen saturation below 85% - especially if it drops suddenly, even with oxygen support.

- High carbon dioxide (pCO2 over 50 mmHg) - this is what’s really poisoning the body, but it’s invisible without blood tests or capnography.

- Extreme drowsiness or confusion - not just tired. This is someone who can’t be woken up properly.

- Slow heart rate (bradycardia) - though some patients get a fast heart rate first, which can mislead.

- Nausea, vomiting, or dizziness - common side effects that often appear before breathing slows.

Here’s what most people miss: supplemental oxygen can hide the danger. If someone is on oxygen, their SpO2 might stay at 95% while CO2 builds up to toxic levels. That’s why pulse oximetry alone isn’t enough. Capnography - measuring exhaled CO2 - is the gold standard when oxygen is being used. It catches problems 10-15 minutes before oxygen drops.

Who’s at highest risk - and why it’s not just addicts

The myth that only people with substance use disorders get respiratory depression is dangerous. In fact, the majority of OIRD cases happen in patients prescribed opioids for pain.

- Older adults (over 60) - 3.2 times more likely. Their lungs are weaker, metabolism slows, and they often take multiple drugs.

- Opioid-naïve patients - those who’ve never taken opioids before. Their bodies haven’t built tolerance. A single dose can be enough.

- Women - 1.7 times higher risk. Exact reasons aren’t fully understood, but body composition and hormone interactions play a role.

- People on other CNS depressants - benzodiazepines (like Xanax or Valium), alcohol, sleep aids, or antipsychotics. Combining opioids with these increases risk by up to 6.3 times.

- Patients with multiple health conditions - COPD, heart failure, kidney disease, or obesity. Each adds another layer of risk. Two or more conditions? Risk jumps 2.8 times per condition.

- People on fixed-dose schedules - especially after surgery. Giving the same dose every 4 hours, regardless of pain level or response, is a recipe for trouble.

One study found that patients with just two risk factors - say, age 70 and on a benzodiazepine - had a 14.7-fold higher chance of respiratory depression than someone with none. This isn’t about addiction. It’s about physiology.

How hospitals miss the signs - and what you can do

Even in hospitals, OIRD slips through the cracks. Why?

- Alarm fatigue - nurses hear dozens of alarms an hour. Many turn off or ignore them. One survey found 68% of units suffer from this.

- Infrequent checks - vital signs checked every 4 hours? That means a patient is unmonitored 96% of the time. A person can go from normal to unresponsive in under 30 minutes.

- Lack of training - only 42% of nurses can correctly identify early signs in simulation tests.

- No risk assessment - only 31% of hospitals use validated tools to screen patients before giving opioids.

Here’s what works: Hospitals that reduced OIRD by 47% did three things:

- Used continuous monitoring for high-risk patients - capnography + pulse oximetry, with alarms set at respiratory rate under 10 and SpO2 under 90%.

- Put pharmacists in charge of opioid dosing - they adjust based on weight, age, kidney function, and prior opioid use.

- Trained every staff member - from nurses to orderlies - to recognize the subtle signs, not just the obvious ones.

If you’re caring for someone on opioids at home, ask: Are they on continuous monitoring? Are they getting checked every hour after a dose? Is naloxone available? If the answer is no, push for it.

Naloxone: The lifesaver that’s often misused

Naloxone reverses opioid effects - fast. But it’s not a magic bullet.

It works by kicking opioids off brain receptors. But if you give too much, you can trigger sudden, severe withdrawal: vomiting, shaking, heart racing, even cardiac arrest. That’s why dosing matters. In cancer patients, reversing pain control can cause unbearable suffering. In others, it’s life-saving.

The key is titration: give small doses, wait, watch. Start with 0.4 mg IV or intranasal. If no response in 2-3 minutes, give more. Don’t dump the whole vial. Keep monitoring for at least 2 hours after - naloxone wears off faster than most opioids. Breathing can stop again.

Keep naloxone in homes where opioids are used. Keep it in cars. Keep it in nursing homes. It’s not just for addicts. It’s for grandmas on pain meds, kids after wisdom teeth removal, anyone on a new opioid prescription.

What’s changing - and what still isn’t

There’s progress. In 2023, the FDA approved the Opioid Risk Calculator - a tool that uses 12 factors (age, weight, kidney function, meds, sleep apnea) to predict individual risk with 84% accuracy. Some hospitals now use AI monitors that predict respiratory depression 15 minutes before symptoms appear.

But adoption is slow. Only 22% of U.S. hospitals meet full safety guidelines. Community hospitals? Just 14%. Medicare now treats severe OIRD as a “never event” - meaning hospitals don’t get paid for treating it. That’s pushing change, but not fast enough.

Future solutions are coming: new opioid drugs designed to relieve pain without suppressing breathing, genetic tests to find people at higher risk, and national reporting systems to track every case. But none of that helps today.

What you need to do right now

If you or someone you care for is taking opioids:

- Know the signs - slow, shallow breathing is the #1 red flag.

- Ask if they’re on continuous monitoring - especially if they’re on oxygen or have risk factors.

- Insist on naloxone being available - and know how to use it.

- Never give opioids with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or sleep meds - it’s a lethal combo.

- After the first dose, watch for 2 hours. That’s when risk is highest.

- Don’t assume “they’re just sleepy.” If they’re hard to wake, call for help immediately.

Respiratory depression isn’t a mystery. It’s a pattern. And patterns can be broken - if you know what to look for. The next time someone says, “They’re just sleeping,” ask: Is their breathing slow? Is it shallow? Are they still breathing at all?

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you have respiratory depression without using opioids?

Yes. Other medications like benzodiazepines (e.g., Xanax, Valium), barbiturates, sleep aids like zolpidem, alcohol, and even some muscle relaxants can cause respiratory depression. The mechanism is similar - they all depress the central nervous system. The risk multiplies when combined with opioids, but even one drug alone can be enough in high doses or in vulnerable people.

Is pulse oximetry enough to detect opioid-induced respiratory depression?

No, not on its own. Pulse oximetry measures oxygen in the blood, but it doesn’t detect rising carbon dioxide. A patient can have normal oxygen levels while CO2 builds to dangerous levels - especially if they’re on supplemental oxygen. Capnography, which measures exhaled CO2, is the only reliable method in these cases. For patients not on oxygen, pulse oximetry is still useful, but it’s not foolproof.

How long does it take for respiratory depression to become life-threatening?

It can happen in as little as 10 to 30 minutes after a dose, especially in opioid-naïve patients or when combined with other depressants. The process is gradual - breathing slows, then becomes shallow, then irregular. But once oxygen saturation drops below 85% and CO2 rises above 60 mmHg, brain damage can begin. Time is critical.

Can you develop tolerance to respiratory depression like you do to pain relief?

Partially. Tolerance to the pain-relieving effects of opioids develops faster than tolerance to respiratory depression. That means someone might need higher doses to control pain, but their breathing remains suppressed. This creates a dangerous gap - they feel fine, but their body is still at risk. This is why long-term opioid users can still overdose.

What should you do if you suspect someone is experiencing respiratory depression?

Call emergency services immediately. If naloxone is available, administer it right away - even if you’re unsure. Don’t wait for confirmation. Try to wake the person. If they’re not breathing, start CPR. Keep giving rescue breaths until help arrives. Even if they wake up, they need medical evaluation - respiratory depression can return after naloxone wears off.

Diksha Srivastava

February 1, 2026 AT 04:00Beth Beltway

February 2, 2026 AT 04:01Marc Bains

February 2, 2026 AT 14:21Diana Dougan

February 2, 2026 AT 17:36Russ Kelemen

February 2, 2026 AT 18:42Lily Steele

February 4, 2026 AT 08:18Amy Insalaco

February 5, 2026 AT 10:22Shawn Peck

February 6, 2026 AT 16:50