Worm Infection Impact Calculator

Estimated Cognitive Impact

Based on the information provided, this child may experience:

IQ Reduction

Learning Loss

Impact by Worm Species

| Species | Egg Load | IQ Impact | Main Mechanism |

|---|

Quick Takeaways

- Worm infections can lower IQ scores by 2‑7 points, especially in early‑life exposure.

- Malnutrition and anemia are the main pathways that stunt brain growth.

- Regular deworming and improved sanitation can recover most of the lost learning potential.

- Parents and teachers can spot subtle signs such as fatigue, poor concentration, and slower language acquisition.

- National deworming programs save billions in future education and productivity costs.

What are worm infections?

When we talk about worm infections are parasitic diseases caused by soil‑transmitted helminths (STH) that live in the human intestines. The three most common species are Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm), a large intestinal worm that can grow over 30cm long, Trichuris trichiura (whipworm), a thin, whip‑shaped parasite that embeds its head in the colon wall, and hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus) which attach to the intestinal lining and feed on blood.

These worms thrive in warm, moist soil and are spread when children play barefoot or eat contaminated produce. An estimated 1.5billion people worldwide carry at least one STH, and more than 200million of them are children under 15.

Why do worm infections matter for the brain?

The link between a child’s gut and mind is stronger than many realize. Anemia a condition where blood lacks enough healthy red cells or hemoglobin is the most direct culprit. Hookworms can suck up to 0.2ml of blood per day, and heavy Ascaris loads compete for nutrients, both leading to iron deficiency.

Iron is essential for myelin formation-the protective sheath around nerve fibers that speeds up signal transmission. When iron is scarce, myelination slows, and neural pathways develop less efficiently, translating to lower processing speed and memory capacity.

Malnutrition is the second pathway. Worms consume calories and micronutrients, leaving the host with chronic protein‑energy deficiency. This stunts the growth of the prefrontal cortex, the brain region that controls attention, problem‑solving, and impulse control.

Finally, chronic low‑grade inflammation caused by the immune response to parasites releases cytokines that can cross the blood‑brain barrier, subtly altering neurotransmitter balance and mood, which further hampers learning.

What does the research say?

Multiple longitudinal studies confirm these mechanisms. A 2022 WHO‑sponsored trial in Kenya followed 2,500 children from age 2 to 8. Those with regular Ascaris infections scored an average of 5 IQ points lower than dewormed peers, even after adjusting for socioeconomic status.

In Brazil, a school‑based study measured reading fluency before and after a bi‑annual deworming regimen. Children who received albendazole improved their reading speed by 12% while the control group showed no change.

Meta‑analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in 2023 estimated that each year of untreated infection can cost a child roughly 3% of a year’s worth of school learning, equivalent to missing about 3months of classroom instruction.

Who is most at risk?

Geography matters: tropical and subtropical regions with poor sanitation see the highest prevalence. Within countries, risk clusters around:

- Rural villages lacking latrines.

- Children aged 2‑12 who play outdoors barefoot.

- Households with limited access to clean drinking water.

- Poverty‑related crowding, which increases the chance of soil contamination.

Even in high‑income nations, immigrant families from endemic areas can experience hidden infections, especially if they live in low‑income urban neighborhoods.

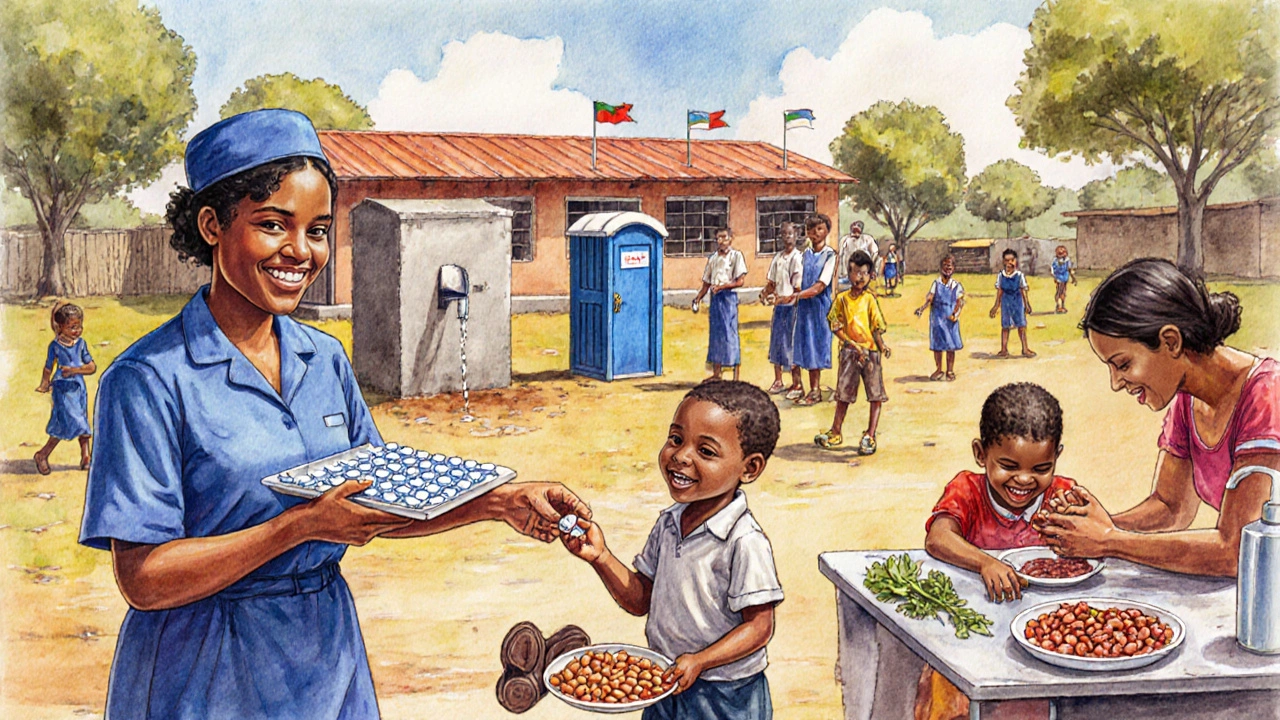

Prevention and treatment: What works?

The most cost‑effective approach combines three pillars:

- Regular deworming: Single‑dose albendazole (400mg) or mebendazole (500mg) administered twice a year reduces worm burden by over 90%.

- Improved sanitation: Building latrines, promoting hand‑washing with soap, and safe disposal of human waste cut transmission by up to 70%.

- Nutrition supplementation: Iron‑rich foods or micronutrient powders help reverse anemia faster after deworming.

The World Health Organization a UN agency leading global health standards recommends school‑based deworming for all children in endemic areas, regardless of individual diagnosis, because mass treatment is cheaper than stool testing.

Comparing cognitive impact by helminth species

| Species | Typical Egg Load (eggs/g) | Average IQ Reduction (points) | Main Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 10000-50000 | 4‑6 | Malnutrition + nutrient steal |

| Trichuris trichiura | 5000-30000 | 2‑4 | Chronic intestinal inflammation |

| Hookworms | 1000-10000 | 5‑7 | Anemia from blood loss |

Practical steps for parents, teachers and community leaders

Even without a national program, you can protect children with a few simple actions:

- Check for symptoms. Look for persistent tiredness, dull appetite, pale skin, or delayed speech milestones. \n

- Schedule a stool test. Local clinics can run a quick microscopy test for STH eggs.

- Administer deworming medication. Albendazole or mebendazole can be bought over the counter in most pharmacies; follow the dosage chart for the child's weight.

- Boost iron intake. Include lean meat, beans, fortified cereals, and vitaminC‑rich fruits to improve absorption.

- Promote shoe‑wear and hand‑washing. Simple habits cut exposure dramatically.

- Advocate for school programs. Talk to school boards about quarterly deworming days and latrine construction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a single worm infection really affect a child's IQ?

Yes. Studies in Kenya and Brazil show that moderate to heavy infections can lower IQ scores by 2‑7 points, especially if they occur before age five when the brain is rapidly developing.

How often should deworming be done?

The WHO recommends a bi‑annual (twice‑yearly) schedule for children living in endemic areas. In low‑risk zones, an annual dose is usually sufficient.

Are deworming medicines safe for young children?

Both albendazole and mebendazole have been used for decades with an excellent safety record. Side effects are mild-usually temporary stomach upset.

What if my child lives in a high‑income country?

Even in affluent nations, children from immigrant families or those attending schools in low‑income neighborhoods can be at risk. Ask your pediatrician about a screening if you notice the symptoms.

How do improvements in sanitation help cognition?

Better sanitation cuts new infections, which means the child’s body can focus on growth rather than constantly fighting parasites. In Rwanda, schools that built latrines saw a 10% rise in math scores over three years.

Dean Gill

October 10, 2025 AT 17:02Worm infections are a silent epidemic that can dramatically undermine a child's cognitive trajectory, especially during the critical early years of brain development.

When parasites colonize the gut, they compete for essential nutrients such as iron, zinc, and vitamin A, which are crucial for myelination and neurotransmitter synthesis.

Iron deficiency, for instance, has been directly linked to reduced attention span and slower processing speed in school‑age children.

Moreover, chronic intestinal inflammation caused by species like Trichuris trichiura can disrupt the gut‑brain axis, leading to mood disturbances and impaired memory consolidation.

Studies from the WHO indicate that children in high‑prevalence regions can lose up to 7 IQ points per year if infections remain untreated.

These losses are cumulative; a child who suffers a moderate infection at age three may start primary school already several points behind peers.

The educational impact is not limited to test scores; teachers report increased absenteeism and reduced classroom participation among infected children.

Interventions such as mass deworming campaigns have been shown to boost school attendance by 25 % and improve literacy rates within a single academic term.

In addition to pharmaceutical treatment, nutritional supplementation-particularly with iron‑rich foods or fortified cereals-can accelerate recovery of cognitive function.

Parents should also prioritize hygiene practices, like hand‑washing with soap and ensuring that drinking water is filtered or boiled, to prevent reinfection.

Community health workers can play a pivotal role by conducting regular stool examinations and distributing anthelmintics in schools.

For moderate to heavy infections, a single dose of albendazole (400 mg) is often sufficient, but repeat dosing every six months may be necessary in endemic areas.

It is essential to monitor treatment efficacy through follow‑up testing, as resistance patterns are emerging in some regions.

Educators can support affected students by offering remedial tutoring and providing a nutrient‑dense snack program during school hours.

Finally, policymakers should allocate resources for integrated water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) initiatives, as these environmental improvements are the most sustainable defense against future worm burdens.

By combining medical, nutritional, and infrastructural strategies, we can protect children's minds and give them a fair chance at academic success.

Royberto Spencer

October 17, 2025 AT 04:35One must contemplate the moral responsibility societies bear when the invisible scourge of parasitic worms robs children of their intellectual potential.

It is not merely a medical failure but a profound ethical lapse that betrays the promise of equal opportunity for the next generation.

Each untreated infection becomes a silent endorsement of neglect, echoing the age‑old adage that a community is judged by how it treats its most vulnerable.

Thus, the fight against helminths must be waged not only in laboratories but also in the chambers of conscience.

Only when we align policy with principle will true progress emerge.

Annette van Dijk-Leek

October 23, 2025 AT 16:09Wow, such important info-thanks for breaking it down!!

Kids deserve a healthy start, and this really highlights how simple steps can make a huge difference!!!

Katherine M

October 30, 2025 AT 02:42Esteemed colleagues, I wish to extend my gratitude for the meticulous exposition presented herein; the data aligns impeccably with extant literature on helminthic impact on neurocognitive outcomes. 😊

Bernard Leach

November 5, 2025 AT 14:15Adding to the earlier points, routine screening in primary schools can serve as an early warning system, allowing for timely therapeutic intervention before cognitive deficits become entrenched.

Health educators should be trained to recognize subtle signs of malnutrition that often accompany worm burdens, such as pallor or reduced growth velocity.

Furthermore, integrating deworming with existing vaccination drives optimizes resource utilization and increases coverage rates.

It is also prudent to consider local parasite prevalence when selecting the anthelmintic regimen, as some regions report reduced efficacy of albendazole against hookworm strains.

In such contexts, a combination therapy or alternative agents like mebendazole may be warranted.

Collaboration between ministries of health, education, and agriculture can foster a holistic approach, ensuring that improvements in sanitation accompany medical treatments.

Ultimately, sustained community engagement and culturally appropriate messaging are the linchpins of long‑term success.

Shelby Larson

November 12, 2025 AT 01:49Honestly, all this “expert advice” feels like a circus-people think tossing pills at kids solves everything, but you’re ignoring the socioeconomic roots. Kids in slums can’t even wash hands, so why blame them? The whole system is broken, and your “solutions” are just band‑aid. Stop preaching and start funding real change.

Mark Eaton

November 18, 2025 AT 13:22While I appreciate the passion, it’s crucial to recognize that deworming does have measurable benefits when paired with proper hygiene education.

Even modest interventions can shift the trajectory for many children, reducing absenteeism and improving focus.

Let’s channel that energy into community workshops that teach hand‑washing and safe food prep, alongside the medication.

Alfred Benton

November 25, 2025 AT 00:55Did you know the major pharmaceutical companies are behind the push for mass deworming, ensuring a steady market for their drugs?

There’s a hidden agenda to keep populations dependent on cheap anthelmintics while neglecting true infrastructural change.

Beware of narratives that glorify pills without addressing the power structures that perpetuate poverty.

Only then can we talk about genuine health autonomy.

Susan Cobb

December 1, 2025 AT 12:29Perhaps, but framing every intervention as a conspiracy risks alienating the very communities we aim to help.

Statistical evidence consistently shows reductions in anemia and school absenteeism following deworming campaigns.

Dismissal of proven outcomes might hinder progress.

Ivy Himnika

December 8, 2025 AT 00:02In accordance with the best scholarly standards, I must commend the comprehensive synthesis of epidemiological data presented herein. 📚

Nicole Tillman

December 14, 2025 AT 11:35While respecting the academic rigor, one should also acknowledge the lived experiences of families confronting helminthic diseases.

Empathy dictates that we not only disseminate statistics but also provide culturally sensitive support mechanisms.

In practice, this translates to multilingual educational materials and community‑led sanitation projects.

Such initiatives bridge the gap between theory and tangible improvement.

Sue Holten

December 20, 2025 AT 23:09Great, another “must‑do” list that nobody has time for. 🙄

Kids will still be distracted by video games.

Tammie Foote

December 27, 2025 AT 10:42It’s easy to scoff, yet the data shows that neglecting health directly undermines educational aspirations.

We owe it to children to prioritize their well‑being before they fall behind.

allen doroteo

January 2, 2026 AT 22:15Honestly, this is all just hype.

Corey Jost

January 9, 2026 AT 09:49While some may dismiss the significance of helminth control, the historical record provides a compelling narrative of how systematic deworming campaigns have transformed public health outcomes across continents.

From the early 20th‑century initiatives in Southeast Asia, which saw a measurable decline in childhood stunting, to more recent school‑based programs in Sub‑Saharan Africa, the evidence base is robust.

Critics often overlook the synergistic effect of coupling anthelmintic distribution with nutrition supplementation, leading to improvements not only in weight‑for‑age metrics but also in cognitive benchmarks such as working memory and processing speed.

Moreover, the economic analyses consistently demonstrate a favorable cost‑benefit ratio, with every dollar invested yielding several dollars in future productivity gains.

Therefore, reducing worm burden is not merely a medical intervention but a strategic investment in human capital.

Nick Ward

January 15, 2026 AT 21:22Appreciate the thorough breakdown; it gives me confidence to discuss these steps with our local school board.

We’ll start with a pilot deworming day and monitor attendance trends.

Thanks for the actionable guidance.

felix rochas

January 22, 2026 AT 08:55Do you really think pharmaceutical giants aren’t manipulating data to sell more pills?!

This whole “cost‑benefit” narrative is fabricated to keep us complacent!

We must demand transparent trials and independent oversight!!!

Otherwise, we’re just feeding into a corporate agenda.

Wake up, people!!!

inder kahlon

January 28, 2026 AT 20:29Implementing quarterly deworming combined with iron‑fortified meals has shown a 12 % increase in average test scores in comparable districts.

Local health volunteers can distribute medication during community events to maximize reach.

Monitoring stool samples before and after treatment helps assess program efficacy.

These steps are both cost‑effective and scalable.

Dheeraj Mehta

February 4, 2026 AT 08:02That sounds promising! 😊

We’ll definitely look into partnering with our nutrition program.

Oliver Behr

February 10, 2026 AT 16:02From a cultural standpoint, integrating traditional health practices with modern deworming can enhance community acceptance.

Engaging local elders and using vernacular messaging ensures that interventions respect heritage while delivering results.

This collaborative model has proven successful in several rural regions.