Gout Risk Estimator

Estimate Your Gout Risk

This tool estimates your uric acid risk based on key factors. Remember, this is for informational purposes only - consult your doctor for medical advice.

Your Estimated Risk

Estimated Serum Urate

Key Risk Factors

Actionable Recommendations

Quick Takeaways

- Elevated gout risk starts when uric acid builds up in the bloodstream.

- Kidney inefficiency, genetics, and a diet high in purines are the top triggers.

- Acute flare‑ups can be identified by a sudden, painful swelling in a joint, most often the big toe.

- Blood tests measuring serum urate, combined with clinical assessment, confirm the diagnosis.

- Long‑term control relies on lifestyle tweaks, hydration, and medications such as allopurinol or colchicine.

What Is Uric Acid and Why Does It Matter?

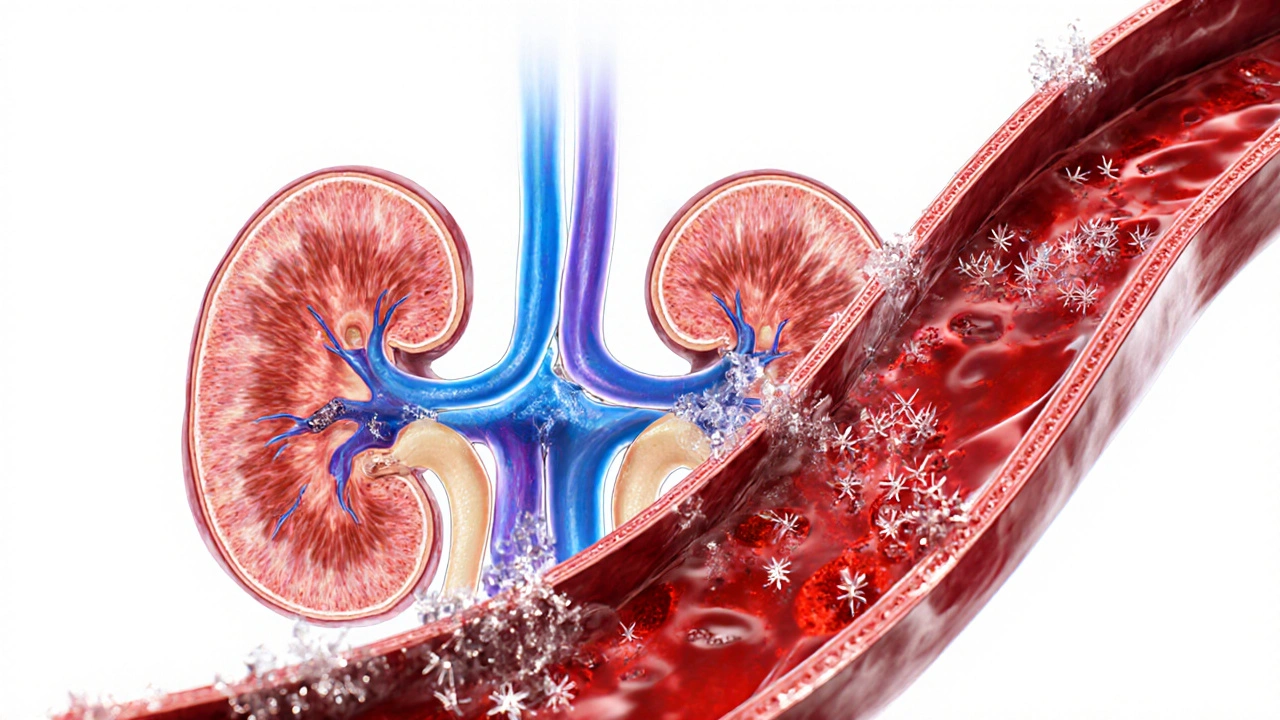

When your body breaks down purines organic compounds found in many foods and in your own cells, it creates a waste product called uric acid a naturally occurring antioxidant that circulates in the blood. Under normal circumstances, the kidney the organ that filters blood and excretes waste removes most of it through urine.

If the kidneys can’t keep up, or if you produce too much uric acid, the level in your blood climbs. This condition is medically called hyperuricemia serum urate levels above 6.8 mg/dL in women or 7.0 mg/dL in men. Not everyone with hyperuricemia gets gout, but the risk jumps dramatically once the threshold is crossed.

How High Uric Acid Leads to Gout

When uric acid saturates the blood, it can crystallize. The tiny needle‑shaped crystals settle in joints, tendons, and surrounding tissues. The immune system spots these crystals as foreign invaders, triggering an inflammatory response. The resulting swelling, heat, and excruciating pain define a gout flare‑up.

These attacks most often hit the big toe joint medial metatarsophalangeal joint, a common early site for crystal deposition, but they can affect ankles, knees, elbows, and even the fingers.

Key Risk Factors Beyond Diet

- Kidney function: Chronic kidney disease reduces uric acid clearance, raising serum levels.

- Genetics: Family history can be a strong predictor; certain gene variants affect urate transport.

- Body weight: Obesity increases production and reduces excretion of uric acid.

- Medications: Loop diuretics, low‑dose aspirin, and some immunosuppressants raise urate.

- Alcohol: Beer and spirits contain purines and hinder renal elimination.

Dietary Triggers: Foods High in Purines

Understanding which foods spike uric acid helps you dodge flare‑ups. Below is a quick comparison of common purine‑rich foods items that contribute significantly to serum urate when consumed in excess.

| Food | Purine Level (mg per 100g) | Gout Risk Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Organ meats (liver, kidney) | 200‑300 | Very High |

| Anchovies, sardines | 150‑250 | High |

| Red meat (beef, pork) | 100‑150 | Moderate |

| Legumes (beans, lentils) | 80‑120 | Low‑Moderate |

| Dairy (low‑fat milk, yogurt) | 20‑30 | Low |

| Eggs | 10‑15 | Very Low |

Swap high‑purine options with low‑purine alternatives like low‑fat dairy, fruits, and whole grains to keep uric acid in check.

How Doctors Diagnose Gout

The first step is a blood test measuring serum urate concentration. Elevated levels confirm hyperuricemia but don’t guarantee gout. The definitive test is joint aspiration: a needle draws fluid from the inflamed joint, and a microscope looks for the characteristic needle‑shaped urate crystals.

Imaging such as ultrasound or dual‑energy CT can also spot crystal deposits when aspiration isn’t feasible.

Managing Gout: Lifestyle and Medication

Effective control blends daily habits with targeted drugs.

Hydration and Weight Management

- Drink at least 2‑3L of water per day; urine dilution helps excrete uric acid.

- Aim for a gradual weight loss of 0.5kg per week if you’re overweight; each kilogram lost can lower serum urate by roughly 0.1mg/dL.

Medication Options

- Allopurinol: a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that reduces uric acid production. Start low (100mg daily) and titrate up to the target urate <7mg/dL.

- Febuxostat: another xanthine oxidase inhibitor, useful when allopurinol isn’t tolerated.

- Colchicine: works fast to curb inflammation during an acute flare. Dose depends on kidney function.

- NSAIDs (e.g., naproxen) for short‑term pain relief, provided there are no contraindications.

- Corticosteroids (oral or intra‑articular) for patients who can’t take NSAIDs or colchicine.

Preventing Future Attacks

Once uric acid is under control, maintain the target level year‑round. Skipping medication even for a few weeks can cause a rebound rise and trigger a flare.

When to Seek Medical Help

If you notice sudden, intense joint pain-especially at night-don’t wait. Early treatment shortens the attack, reduces joint damage, and prevents crystal buildup.

Also contact a clinician if you develop kidney stones, notice swelling in multiple joints, or if lifestyle changes aren’t lowering your urate levels.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I cure gout by diet alone?

Diet alone can lower uric acid but rarely eliminates gout completely. Most patients need a combination of dietary changes and medication to stay flare‑free.

Why does the big toe get hit first?

The big toe joint stays cooler than the rest of the body, encouraging uric acid crystals to form there first. Its limited blood flow also makes inflammation more noticeable.

Is alcohol really that bad for gout?

Yes. Beer contains purines, and spirits reduce renal excretion of urate. Cutting back can drop serum urate by 0.3‑0.5mg/dL within weeks.

How fast does colchicine work?

Colchicine can start relieving pain within 12‑24hours if given early in the flare. It’s most effective when taken within the first 12 hours of symptom onset.

Can gout cause permanent joint damage?

Repeated attacks can erode cartilage and bone, leading to chronic arthritis. Prompt treatment and long‑term urate control prevent this progression.

Allison Sprague

October 14, 2025 AT 14:10Uric‑acid thresholds are not mere numbers; they delineate a metabolic tipping point where benign hyperuricemia can morph into full‑blown gout. The article glosses over the fact that renal clearance variability accounts for a sizable portion of that transition. Moreover, the risk matrix omits a discussion of gender‑specific pharmacokinetics, which is a glaring oversight. Readers would benefit from a more granular breakdown of how body mass index interacts with purine metabolism, rather than the superficial list of “high‑purine foods”.

leo calzoni

October 19, 2025 AT 05:16Stop treating gout like a hobby project. The body doesn’t care how much you read; it cares about excess purines and neglected kidneys. Your diet is the culprit, not some mystical “threshold” you can ignore.

KaCee Weber

October 23, 2025 AT 20:23Reading through the overview, I couldn’t help but notice how the information weaves together both science and lifestyle advice in a surprisingly cohesive tapestry.

First, the explanation of how uric acid crystallizes in the joint space paints a vivid picture that even the most layperson can visualize.

Second, the inclusion of kidney function as a pivotal factor reminds us that gout is never an isolated joint problem.

Third, the dietary chart, while helpful, could be expanded to include cultural staples that many readers rely on, such as lentils in South Asian cuisines.

Fourth, the recommendation to increase water intake to two to three liters aligns perfectly with the physiological need to dilute serum urate.

Fifth, the advice on gradual weight loss is both realistic and evidence‑based, considering that each kilogram can shave off roughly 0.1 mg/dL of uric acid.

Sixth, the brief nod to medications like allopurinol acknowledges that lifestyle alone may not suffice for everyone.

Seventh, the article rightly cautions that hyperuricemia does not guarantee gout, which is a nuance many lay articles miss.

Eighth, I appreciate the mention of ultrasound and dual‑energy CT as diagnostic adjuncts, because joint aspiration isn’t always practical.

Ninth, the list of risk factors includes genetics, a reminder that family history can predispose individuals regardless of diet.

Tenth, the suggestion to avoid high‑purine foods like organ meats and anchovies is spot‑on, yet I would add that moderate consumption may still be tolerable for some.

Eleventh, the tone remains encouraging throughout, which helps readers feel empowered rather than chastised.

Twelfth, the use of simple language mixed with occasional scientific terms strikes a balance that educates without alienating.

Thirteenth, the formatting with bullet points and tables makes quick reference painless, especially on mobile devices.

Finally, I’m left feeling better equipped to discuss gout with my doctor, and that’s exactly the point of a good health guide 😊👍.

jess belcher

October 28, 2025 AT 10:30Uric acid builds up when kidneys lag behind the body’s purge needs

Eating less red meat helps

Stay hydrated and the numbers drop

Sriram K

November 2, 2025 AT 01:36For anyone tracking their serum urate, it’s useful to know that a 5 % reduction in body weight can translate to a 0.5 mg/dL drop in uric acid levels, which often moves a patient from the “high” to the “moderate” risk category. Additionally, incorporating low‑fat dairy into daily meals has been shown to increase urinary excretion of uric acid, providing a simple dietary tweak. If you’re on a thiazide diuretic, discuss with your physician whether a switch to a potassium‑sparing alternative might mitigate medication‑induced hyperuricemia. Regular monitoring-every three to six months-ensures that any upward trend is caught early, allowing timely adjustments in lifestyle or pharmacotherapy.

Deborah Summerfelt

November 6, 2025 AT 16:43Gout isn’t just a rich‑people’s problem.

Maud Pauwels

November 11, 2025 AT 07:50I think the article does a decent job of covering the basics but could use a bit more detail on how alcohol really spikes uric acid levels especially beer which is often overlooked

Scott Richardson

November 15, 2025 AT 22:56America’s diet is killing us with cheap meat and soda you can’t blame anyone else

Laurie Princiotto

November 20, 2025 AT 14:03Honestly the “quick takeaways” read like a corporate press release 😒 the real pain of gout is missing from the list

June Wx

November 25, 2025 AT 05:10Listen, if you think swapping shrimp for chicken will magically erase gout, you’re living in a fantasy world.

kristina b

November 29, 2025 AT 20:16The pathophysiology of gout, as delineated in the present discourse, commands a reverence that is seldom afforded to other metabolic derangements. It is incumbent upon the learned reader to appreciate that uric acid, while a mere byproduct of purine catabolism, assumes a quasi‑virulent character when supersaturation precipitates crystalline deposition. Such deposition, most frequently observed within the first metatarsophalangeal joint, elicits an inflammatory cascade of such vigor that it rivals the most tempestuous of autoimmune assaults. The author’s exposition rightly underscores the duality of renal clearance and dietary intake as pivotal determinants of serum urate concentration. Nevertheless, the omission of a nuanced discussion regarding the pharmacogenomics of allopurinol metabolism represents a lacuna that warrants rectification. From a therapeutic standpoint, the recommendation to augment aqueous intake aligns impeccably with the principle of dilutional excretion, thereby attenuating supersaturation. Equally, the counsel to pursue incremental weight reduction is buttressed by robust epidemiological evidence linking adiposity to heightened urate synthesis. To the scholar seeking comprehensive guidance, an appraisal of adjunctive agents such as febuxostat and lesinurad would greatly enhance the article’s clinical utility. Moreover, the sociocultural implications of purine‑rich culinary traditions merit a respectful yet critical examination, lest the discourse descend into prescriptive monolithism. In sum, the treatise furnishes a commendable foundation, yet the discerning clinician will find ample opportunity to embellish its scaffolding with deeper insight.

Ida Sakina

December 4, 2025 AT 11:23In conclusion the moral imperative is clear; let us not neglect the silent suffering of those burdened by hyperuricemia; only through vigilant stewardship of diet and medicine can we hope to alleviate this affliction