Drug-Gene Interaction Checker

Select a medication to see if genetic testing could help avoid severe side effects.

Have you ever taken a medication that made you feel worse instead of better? Maybe you got dizzy on a common blood pressure pill, or broke out in a rash after a simple antibiotic. For some people, these reactions aren’t random-they’re written in their DNA. Genetic factors play a major role in why certain drugs cause severe side effects in some people but not others. This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now in clinics, hospitals, and pharmacies around the world.

Why Your Genes Decide How You React to Drugs

Your body doesn’t treat every drug the same way. What happens after you swallow a pill depends heavily on how your genes control its journey through your system. Two big systems are involved: how fast your body breaks down the drug (pharmacokinetics), and how the drug interacts with its target in your body (pharmacodynamics).

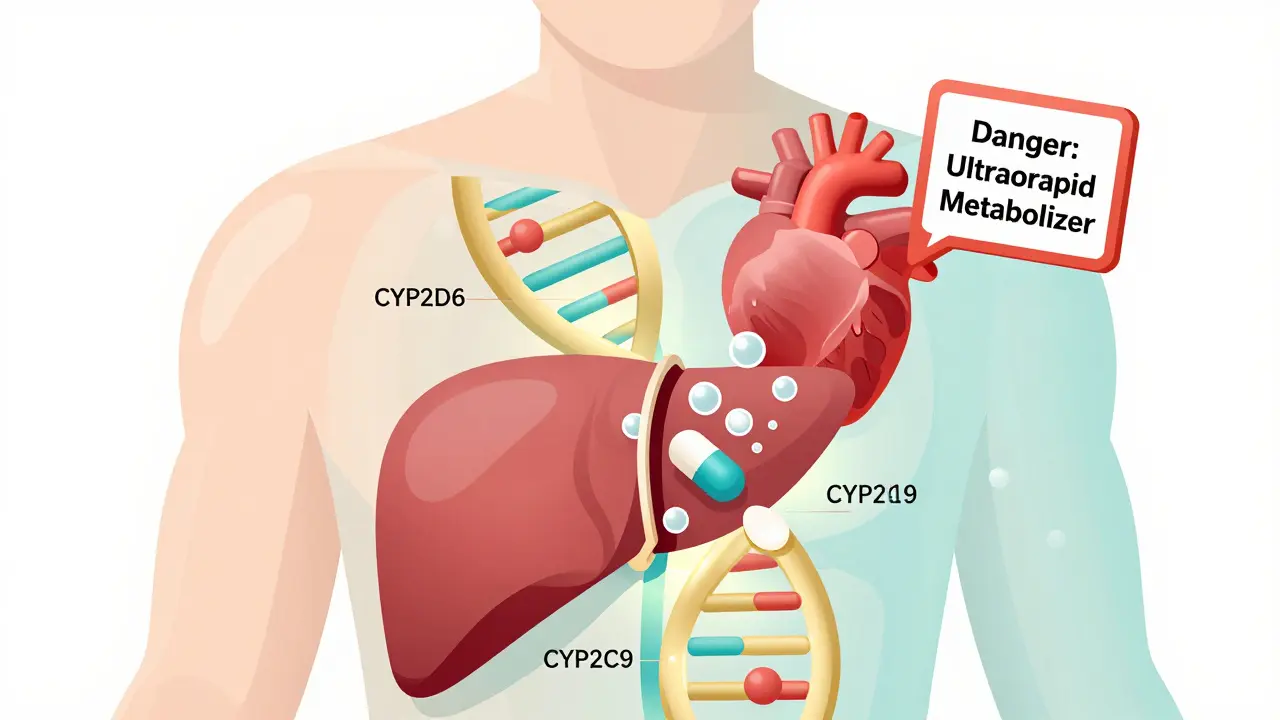

One of the most important players is the cytochrome P450 enzyme family, especially CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19. These enzymes act like molecular scissors, cutting drugs into pieces so your body can get rid of them. But not everyone has the same scissors. Some people have versions of these genes that work too slowly (poor metabolizers), others have versions that work too fast (ultrarapid metabolizers), and some have versions that barely work at all.

Take codeine, for example. It’s a weak painkiller that your body turns into morphine using CYP2D6. If you’re an ultrarapid metabolizer, you turn codeine into morphine so quickly that even a normal dose can cause dangerous breathing problems. That’s why the FDA added a black box warning: nursing mothers who are ultrarapid metabolizers can pass deadly levels of morphine to their babies through breast milk. This isn’t rare. About 1 in 10 people of European descent are ultrarapid metabolizers of CYP2D6.

When Your DNA Triggers Life-Threatening Reactions

Some genetic risks aren’t about metabolism-they’re about your immune system going haywire. The most dramatic example is the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant. If you carry this variant and take carbamazepine (used for seizures and nerve pain), you have a 100 to 150 times higher chance of developing Stevens-Johnson Syndrome or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis-rare but deadly skin conditions that cause massive blistering and tissue death.

Because of this, doctors in countries with high rates of this variant-like Thailand, Malaysia, and parts of China-are required to test patients before prescribing carbamazepine. If you test positive, you’re given a different drug. The good news? If you don’t have HLA-B*15:02, your risk of this reaction is nearly zero. That’s one of the strongest negative predictive values in all of medicine.

Another example is HLA-B*57:01 and the HIV drug abacavir. About 5% of people who carry this variant will get a severe allergic reaction. But here’s the twist: almost everyone who gets the reaction has the gene. So testing for HLA-B*57:01 before giving abacavir prevents nearly all cases of this reaction. It’s one of the most successful examples of using genetics to avoid harm.

Why Some Side Effects Are Easier to Predict Than Others

Not all side effects are created equal when it comes to genetics. A 2024 study in PLOS Genetics found that cardiovascular side effects-like irregular heartbeat, high blood pressure, or rapid pulse-are the most predictable based on genetics. Why? Because many drugs affect the same biological pathways that naturally vary between people due to inherited traits. For example, if your body already has a genetic tendency toward long QT intervals (a heart rhythm issue), taking certain antibiotics or antidepressants can push you over the edge into a dangerous arrhythmia called torsades de pointes.

Researchers found that about 5% of people who develop drug-induced torsades have hidden mutations in genes like KCNQ1, KCNH2, or SCN5A-genes linked to inherited long QT syndrome. These mutations might never cause problems on their own, but add a drug and suddenly you’re at risk.

On the flip side, gastrointestinal side effects-like nausea, diarrhea, or stomach pain-are much harder to predict with genetics. Their positive predictive value is under 10%. That means even if you have a gene linked to these reactions, you’re still unlikely to get them. It’s likely that diet, stress, gut bacteria, and other environmental factors play bigger roles here.

Warfarin, Statins, and the Math of Genetic Dosing

Warfarin, a blood thinner used to prevent strokes and clots, is one of the most studied drugs in pharmacogenomics. Its dose varies wildly between people-some need 1 mg a day, others need 10 mg. Why? Two genes explain most of it: VKORC1 and CYP2C9.

People with the VKORC1 -1639G>A variant need lower doses because their bodies are more sensitive to warfarin. Those with CYP2C9 variants break down the drug slower, so it builds up. Together, these two variants explain up to 40% of why people need different doses. In fact, many hospitals now use genetic testing to start patients on the right dose from day one, instead of guessing and adjusting over weeks.

Same thing with statins-the cholesterol-lowering drugs. The SLCO1B1 gene controls how your liver takes up these drugs. People with a specific variant (called *5) have a 4.5 times higher risk of muscle pain and damage (myopathy). Testing for this variant can help doctors choose a safer statin or lower the dose before problems start.

Who’s Getting Tested-and Who’s Being Left Behind

Even though the science is solid, most people still aren’t getting tested. In the U.S., only about 10-15% of actionable pharmacogenetic variants are used in routine care. Why? For starters, most doctors haven’t been trained to interpret genetic reports. A 2023 survey found that nearly 70% of physicians felt unprepared to use this data.

Cost is another barrier. Comprehensive genetic tests cost between $250 and $500. Insurance doesn’t always cover them, especially if they’re done before you even need the drug. Medicare Advantage plans covered preemptive testing in only 28% of cases in 2023. That means many patients wait until they have a bad reaction before anyone thinks to check their genes.

And then there’s representation. Over 80% of pharmacogenetic studies have been done in people of European descent. But genetic variants are more diverse in African, Indigenous, and Asian populations. For example, the CYP2D6 gene has over 100 known variants, but most clinical tests only check for 10-15 of them. That means people from other backgrounds are more likely to get misclassified-leading to wrong dosing or missed risks.

Real Stories, Real Impact

At Vanderbilt’s PREDICT program, which started testing patients for pharmacogenetic variants in 2011, doctors changed prescribing decisions for over 12% of patients based on genetic results. Most of those changes were to avoid a drug entirely or lower the dose. One patient, a 62-year-old woman taking tamoxifen for breast cancer, had her dose delayed for three weeks while waiting for CYP2D6 results. When they came back, she was a poor metabolizer. Her doctor switched her to a different drug. She avoided the crippling nausea her sister had suffered. “It saved my quality of life,” she said.

But it’s not perfect. Some people get false positives-like being told they have HLA-B*15:02 when they don’t. That can lead to doctors refusing to prescribe life-saving seizure medications. One advocacy group documented 178 cases where people with epilepsy were denied carbamazepine because of incorrect genetic testing. That’s a failure of interpretation, not the science itself.

What’s Next? The Future of Personalized Dosing

The FDA now requires genetic testing for 18 drugs, up from just 3 in 2010. By 2027, that number could jump to 35 or more. The All of Us Research Program has already returned genetic results to over 215,000 people, and nearly half of them carry at least one actionable variant.

Researchers are now moving beyond single genes. A new approach called polygenic risk scores looks at dozens of genes at once to predict side effect risk. One 2024 study used a 15-gene score to predict statin-induced muscle pain with 82% accuracy-far better than checking just SLCO1B1 alone.

Eventually, whole-genome sequencing could become routine. The eMERGE Network found that preemptive sequencing identified actionable drug-gene interactions in 91% of participants. That means in the future, your DNA could be checked once at age 18, and your doctor could refer to it every time you get a new prescription.

But we’re not there yet. We still need better training for doctors, more inclusive research, and fairer access to testing. Until then, if you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug before-or if your family has-it’s worth asking: Could this be genetic? It might just save you from the next one.

Can genetic testing prevent all drug side effects?

No, genetic testing can’t prevent all side effects. It only helps with reactions caused by specific gene variants-like those affecting drug metabolism or immune response. Many side effects, like nausea, dizziness, or headaches, are caused by non-genetic factors such as age, diet, other medications, or underlying health conditions. Genetic testing is powerful for certain high-risk reactions, but it’s not a magic shield.

Which drugs require genetic testing before use?

The FDA currently requires or recommends genetic testing for 18 drugs, including abacavir (for HIV), carbamazepine (for seizures), warfarin (blood thinner), codeine (painkiller), and clopidogrel (antiplatelet). The list is growing. Drugs like irinotecan (cancer treatment) and tacrolimus (organ transplant) require testing in other countries like Japan. Always check the drug’s official label or ask your pharmacist.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance?

It depends. Some private insurers cover testing when it’s ordered by a doctor for a specific drug. Medicare covers testing for only 7 out of the 128 gene-drug pairs recognized by the FDA. Most plans don’t cover preemptive testing (done before you need the drug). Costs range from $250 to $500, and out-of-pocket testing through companies like 23andMe or Color Genomics is often not covered unless ordered by a clinician.

How accurate are direct-to-consumer genetic tests for drug reactions?

Many direct-to-consumer tests (like 23andMe) report pharmacogenetic results, but they’re not always reliable for clinical use. The FDA has issued 12 warning letters to companies for overstating accuracy or clinical relevance. These tests often screen for only a few variants and may miss important ones-especially in non-European populations. For medical decisions, always confirm results with a clinical-grade test ordered by a healthcare provider.

Should I get tested before starting a new medication?

If you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug before, or if you’re starting a medication known to have strong genetic risks (like carbamazepine, abacavir, or warfarin), yes. If you’re planning long-term treatment-like antidepressants, blood thinners, or cancer drugs-it’s worth discussing. For healthy people without a history of side effects, testing isn’t yet routine, but that may change as costs drop and evidence grows.

Clay .Haeber

January 14, 2026 AT 14:27Priyanka Kumari

January 14, 2026 AT 15:39Gregory Parschauer

January 14, 2026 AT 22:25Avneet Singh

January 16, 2026 AT 02:28Nelly Oruko

January 17, 2026 AT 01:29vishnu priyanka

January 17, 2026 AT 13:44Angel Tiestos lopez

January 17, 2026 AT 15:13Pankaj Singh

January 18, 2026 AT 02:18Milla Masliy

January 19, 2026 AT 05:15Damario Brown

January 20, 2026 AT 19:35sam abas

January 22, 2026 AT 04:47John Pope

January 24, 2026 AT 00:47Adam Vella

January 24, 2026 AT 23:14